The Mind Is Its Own Place

“When we base our lives on the Mystic Law, the life states that drag us toward suffering and unhappiness move in the opposite, positive direction. It is as if sufferings become the “firewood” that fuels the flames of joy, wisdom and compassion.“

The Principle for Transforming Our Lives

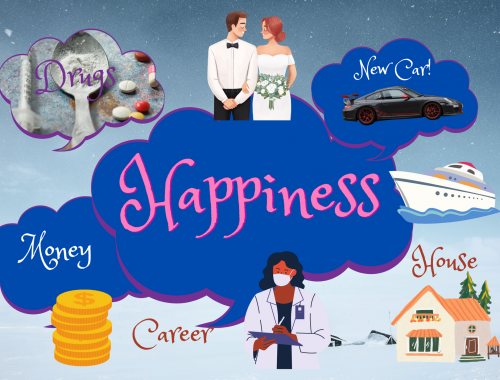

As discussed in chapter one, it is important to seek absolute happiness over relative happiness. How, then, do we go about achieving it? Absolute happiness is not something that is given to us. Based on the principles of Nichiren Buddhism, SGI President Ikeda explains that it can only be attained through our personal inner transformation.

Our lives possess a wide range of possibilities; they can move in a positive or negative direction, and toward either happiness or unhappiness. We may at times find ourselves in the depths of suffering or at the mercy of our desires and instinctual urges. At other times, we may feel calm and content with our lives or feel motivated by compassion to reach out and help those who are suffering.

Buddhism explores these various potential conditions, categorizing them into ten states of life called the Ten Worlds. Among the Ten Worlds, the world of Buddhahood accords with our noblest potential and highest state of life.

Nichiren Daishonin identified the Law permeating the universe and life as Nam-myoho-rengekyo and embodied it in the form of the Gohonzon, the object of devotion, thereby establishing a means by which all people can reveal their innate Buddhahood.

This chapter introduces the basics of the doctrine of the Ten Worlds—the principle that is the key to inner transformation—as well as the significance of the Gohonzon.

President Ikeda discusses the core teaching of Nichiren Buddhism that, through chanting Nam-myoho-renge-kyo with faith in the Gohonzon, we can establish the world of Buddhahood as the foundation of our lives and turn all suffering into nourishment for developing a higher state of life. Further, we can transform not only our own lives but help others do the same, and contribute to the betterment and prosperity of society.

2.1 Heaven and Hell Exist Within Our Own Lives

The way we perceive the world around us is largely influenced by our state of life. In this excerpt, President Ikeda explains that Nichiren Buddhism is a powerful teaching that enables us to elevate our state of life, improve our environment, and actualize genuinely happy lives for ourselves and prosperity for society as a whole, while positively transforming the land in which we live.

President Ikeda’s Guidance

From a speech at the 1st Wakayama Prefecture General Meeting, Kansai Training Center, Wakayama Prefecture, Japan, March 24, 1988.

The English poet John Milton (1608–74) wrote, “The mind is its own place, and in itself ‘Can make a Heav’n of Hell, a Hell of Heav’n.’” This statement, a product of the poet’s profound insight, resonates with the Buddhist teaching of “three thousand realms” in a single moment of life.

How we see the world and feel about our lives is determined solely by our inner life condition. Nichiren Daishonin writes: “Hungry spirits perceive the Ganges River as fire, human beings perceive it as water, and heavenly beings perceive it as amrita. Though the water is the same, it appears differently according to one’s karmic reward from the past.”

(“Reply to the Lay Priest Soya,” The Writings of Nichiren Daishonin, vol. 1, p. 486)

“Karmic reward from the past” refers to our present life state, which is the result of past actions or causes created through our own words, thoughts and deeds. That state of life determines our view of and feelings toward the external world.

The same circumstances may be perceived as utter bliss by one person and unbearable misfortune by another. And while some people may love the place where they live, thinking it’s the best place ever, others may hate it and constantly seek to find happiness somewhere else.

Nichiren Buddhism is a teaching that enables us to elevate our inner state of life, realizing genuinely happy lives for ourselves as well as prosperity for society. It is the great teaching of the “actual three thousand realms in a single moment of life,” making it possible for us to transform the place where we dwell into the Land of Eternally Tranquil Light. 3

Moreover, the good fortune, benefit and joy we gain through living in accord with the eternal Law [of Nam-myoho-renge-kyo] are not temporary. In the same way that trees steadily add growth rings with each passing year, our lives accumulate good fortune that will endure throughout the three existences of past, present and future. In contrast, worldly wealth and fame as well as various amusements and pleasures—no matter how glamorous or exciting they may seem for a time—are fleeting and insubstantial.

2.2 Buddhahood Is the Sun Within Us

In this excerpt, President Ikeda gives a brief overview of the Ten Worlds and their mutual possession—concepts that lie at the heart of the Buddhist philosophy of life. He also underscores how Nichiren Daishonin, through his teaching, established a practice based on faith in the Gohonzon as the means for all people to manifest the highest and noblest state of life, that of Buddhahood.

President Ikeda’s Guidance

Adapted from the dialogue On Life and Buddhism, published in Japanese in November 1986.

Life, which is constantly changing from moment to moment, can be broadly categorized into ten states, which Buddhism articulates as the Ten Worlds. These consist of the six paths—the worlds of hell, hunger, animality, anger, humanity and heaven— and the four noble worlds—the worlds of learning, realization, bodhisattva and Buddhahood. The true reality of life is that it always possesses all ten of these potential states.

None of the Ten Worlds that appear in our lives at any given moment remain fixed or constant. They change instant by instant. Buddhism’s deep insight into this dynamic nature of life is expressed as the principle of the mutual possession of the Ten Worlds.

In his treatise “The Object of Devotion for Observing the Mind,” Nichiren Daishonin illustrates clearly and simply how the world of humanity contains within it the other nine worlds:

When we look from time to time at a person’s face, we find him or her sometimes joyful, sometimes enraged, and sometimes calm. At times greed appears in the person’s face, at times foolishness, and at times perversity. Rage is the world of hell, greed is that of hungry spirits, foolishness is that of animals, perversity is that of asuras, joy is that of heaven [heavenly beings], and calmness is that of human beings. (WND-1, 358)

The nine worlds are continually emerging and becoming dormant within us. This is something that we can see, sense and recognize in our own daily lives.

It is important to note here that the teachings of Buddhism from the very beginning were always concerned with enabling people to manifest the noble and infinitely powerful life state of Buddhahood. And, indeed, that should always be the purpose of Buddhist practice. Focusing on this point, the great teaching of Nichiren, by establishing the correct object of devotion [the Gohonzon of Nammyoho-renge-kyo], sets forth a practical means for revealing our inner Buddhahood. As such, Nichiren Buddhism is a practice open to all people.

A look at history to this day shows that humanity is still trapped in the cycle of the six paths, or lower six worlds. The character for “earth” ( ji) is contained in the Japanese word for “hell” ( jigoku; literally meaning earth prison), imparting the meaning of being bound or shackled to something of the lowest or basest level. Humanity and society can never achieve substantial revitalization unless people give serious thought to casting off the shackles of these lower worlds and elevating their state of life. Even in the midst of this troubled and corrupt world, Buddhism discovers in human life the highest and most dignified potential of Buddhahood.

Though our lives may constantly move through the six paths, we can activate the limitless life force of Buddhahood by focusing our minds on the correct object of devotion and achieving the “fusion of reality and wisdom.”

Buddhahood is difficult to describe in words. Unlike the other nine worlds, it has no concrete expression. It is the ultimate function of life that moves the nine worlds in the direction of boundless value.

Even on cloudy or rainy days, by the time a plane reaches an altitude of about 33,000 feet, it is flying high above the clouds amid bright sunshine and can proceed smoothly on its course. In the same way, no matter how painful or difficult our daily existence may be, if we make the sun in our hearts shine brightly, we can overcome all adversity with calm composure. That inner sun is the life state of Buddhahood.

In one sense, as the Daishonin states in The Record of the Orally Transmitted Teachings, “‘Bodhisattva’ is a preliminary step toward the attainment of the effect of Buddhahood” (p. 87). The world of bodhisattva is characterized by taking action for the sake of the Law, people and society. Without such bodhisattva practice as our foundation, we cannot attain Buddhahood. Buddhahood is not something realized simply through conceptual understanding. Even reading countless Buddhist scriptures or books on Buddhism will not lead one to true enlightenment.

In addition, attaining Buddhahood doesn’t mean that we become someone different. We remain who we are, living out our lives in the reality of society, where the nine worlds—especially the six paths—prevail. A genuine Buddhist philosophy does not present enlightenment or Buddhas as something mysterious or otherworldly.

What is important for us as human beings is to elevate our lives from a lower to a higher state, to expand our lives from a closed, narrow state of life to one that is infinitely vast and encompassing. Buddhahood represents the supreme state of life.

2.3 Establishing the World of n Buddhahood as Our Basic Life Tendency

Based on the principle of the mutual possession of the Ten Worlds, President Ikeda in this excerpt introduces the idea that each of us has a basic or habitual life tendency—a tendency that has been formed through our repeated past actions encompassing speech, thought and deed. He further clarifies that “attaining Buddhahood” means establishing the world of Buddhahood as this basic life tendency.

Yet, even with Buddhahood as our basic life tendency, we will still face the sufferings of the nine worlds that are the reality of our existence. Irrespective of the problems and hardships we may encounter in life, however, compassion, hope and joy arising from the world of Buddhahood will well forth within us. In his treatise “The Object of Devotion for Observing the Mind,” Nichiren Daishonin offers an example of “the nine worlds inherent in Buddhahood” (WND-1, 357), citing the Lotus Sutra passage where Shakyamuni states: “Thus since I attained Buddhahood, an extremely long period of time has passed . . . I have constantly abided here without ever entering extinction . . . Originally I practiced the bodhisattva way, and the life span that I acquired then has yet to come to an end ”(pp. 267–68). We could say that a practical expression of this passage can be found in living our lives with Buddhahood as our basic life tendency.

President Ikeda’s Guidance

Adapted from the dialogue The Wisdom of the Lotus Sutra, published in Japanese in December 1998.

One way to view the principle that each of us is an entity of the mutual possession of the Ten Worlds is to look at it from the perspective of our basic life tendency. While we all possess the Ten Worlds, our lives often lean toward one particular life state more than others—for instance, some people’s lives are basically inclined toward the world of hell, while others tend naturally toward the world of bodhisattva. This could be called the “habit pattern” of one’s life, a predisposition formed through karmic causes that a person has accumulated from the past.

Just as a spring returns to its original shape after being stretched, people tend to revert to their own basic tendency. But even if one’s basic life tendency is the world of hell, it doesn’t mean that one will remain in that state 24 hours a day. That person will still move from one life state to another— for instance, sometimes manifesting the world of humanity, sometimes the world of anger and so on. Likewise, those whose basic life tendency is the world of anger—driven by the desire to always be better than others—will also sometimes manifest higher worlds such as heaven or bodhisattva. However, even if they momentarily manifest the world of bodhisattva, they will quickly revert to their basic life tendency of the world of anger.

Changing our basic life tendency means carrying out our human revolution and fundamentally transforming our state of life. It means changing our mind-set or resolve on the deepest level. The kind of life we live is decided by our basic life tendency. For example, those whose basic life tendency is the world of hunger are as though on board a ship called Hunger. While sailing ahead in the world of hunger, they will sometimes experience joy and sometimes suffering. Though there are various ups and downs, the ship unerringly proceeds on its set course. Consequently, for those on board this ship, everything they see will be colored in the hues of the world of hunger. And even after they die, their lives will merge with the world of hunger inherent in the universe.

Establishing the world of Buddhahood as our basic life tendency is what it means to “attain Buddhahood.” Of course, even with the world of Buddhahood as our basic life tendency, we won’t be free of problems or suffering, because we will still possess the other nine worlds. But the foundation of our lives will become one of hope, and we will increasingly experience a condition of security and joy.

My mentor, second Soka Gakkai president Josei Toda, once explained this as follows:

Even if you fall ill, simply have the attitude: “I’m all right. I know that if I chant to the Gohonzon, I will get well.” Isn’t the world of Buddhahood a state of life in which we can live with total peace of mind? That said, however, given that the nine worlds are inherent in the world of Buddhahood, we might still occasionally become angry or have to deal with problems. Therefore, enjoying total peace of mind doesn’t mean that we have to renounce anger or some such thing. When something worrying happens, it’s only natural to be worried. But in the innermost depths of our lives, we will have a profound sense of security. This is what it means to be a Buddha . . .

If we can regard life itself as an absolute joy, isn’t that being a Buddha? Doesn’t that mean attaining the same life state as Nichiren? Even when faced with the threat of being beheaded, the Daishonin remained calm and composed. If it had been us in that situation, we’d have been in a state of complete panic! When the Daishonin was exiled to the hostile environment of Sado Island, he continued instructing his disciples on various matters and produced such important writings as “The Opening of the Eyes” and “The Object of Devotion for Observing the Mind.” If he didn’t have unshakable peace of mind, he would never have been able to compose such great treatises [under such difficult circumstances].

Our daily practice of gongyo—reciting portions of the Lotus Sutra and chanting Nam-myohorenge-kyo—is a solemn ceremony in which our lives become one with the life of the Buddha. By applying ourselves steadfastly and persistently to this practice for manifesting our inherent Buddhahood, we firmly establish the world of Buddhahood in our lives so that it is solid and unshakable like the earth. On this foundation, this solid stage, we can freely enact at each moment the drama of the nine worlds.

Moreover, kosen-rufu is the challenge to transform the fundamental life state of society into that of Buddhahood. The key to this lies in increasing the number of those who share our noble aspirations.

When we base ourselves on faith in Nichiren Buddhism, absolutely no effort we make is ever wasted.

When we establish Buddhahood as our basic life tendency, we can move toward a future of hope while creating positive value from all our activities in the nine worlds, both past and present. In fact, all of our hardships and struggles in the nine worlds become the nourishment that strengthens the world of Buddhahood in our lives.

In accord with the Buddhist principle that “earthly desires lead to enlightenment,” sufferings (earthly desires, or the deluded impulses of the nine worlds) all become the “firewood” or fuel for gaining happiness (enlightenment, or the world of Buddhahood). This is similar to how our bodies digest food and turn it into energy.

A Buddha who has no connection to the actual sufferings of the nine worlds is not a genuine Buddha—namely, one who embodies the mutual possession of the Ten Worlds. This is the essential message of “Life Span,” the 16th chapter of the Lotus Sutra.

The world of Buddhahood can also be described as a state of life in which one willingly takes on even hellish suffering. This is the world of hell contained in the world of Buddhahood. It is characterized by empathy and hardships deliberately taken on for the happiness and welfare of others, and arises from a sense of responsibility and compassion. Courageously taking on problems and sufferings for the sake of others strengthens the world of Buddhahood in our lives.

The Wisdom for Creating Happiness and Peace Part 1 Chapter 2 August 2014 Living Buddhism